The 2024 hurricane season officially ended on November 30, concluding six months of above-average hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin. The season had it all: superlatively warm ocean water which provided a fertile breeding ground for hurricanes, flooding as far north as Appalachia, and tornados in the Everglades.

At the beginning of the year, some scientists posited that the Saffir-Simpson scale for hurricane intensity should be revised to reflect the intensity of future hurricanes. Given the remarkable storms of 2024—including one hurricane with 180 mile-per-hour (290 kilometer-per-hour) wind speeds—you can see where they’re coming from. Let’s review some of the record-breaking moments of this hurricane season, and see how it lined up with forecasters’ predictions.

Forecasters warned of a record-breaking hurricane season

Unlike the 2023 hurricane season, this year’s weather was forecast to be more tempestuous than normal. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasted between 17 and 25 named storms, while Colorado State University’s seasonal hurricane forecast predicted 23 named storms. Both institutions’ figures were up from 1991 to 2020 averages: 14.4 named storms per year, 7.2 hurricanes per year, and 3.2 major hurricanes per year.

Forecasts aren’t always on the money; despite its average expectations, 2023 ended with the fourth-most-named storms for a season at 20, while the Atlantic basin only had 18 named storms this year. That means there weren’t enough Atlantic tropical cyclones to run through the entire list of predetermined names—the last named storm, Sara, petered out on November 18 after causing severe flooding in Central America. But don’t let the lower total number of named storms in 2024 diminish the severity and lasting impacts of the weather.

The earliest Category 5 storm in recorded history

Hurricane Beryl was the second-named storm of the season, and the first Category 5 hurricane of the year. Beryl was upgraded to a Category 5 storm—classified as a storm with sustained wind speeds exceeding 157 miles per hour (252 kilometers per hour)—on July 2, just three days into hurricane season. That made Beryl the earliest Category 5 on record; the silver medal goes to Hurricane Emily, which achieved Category 5 status on July 17, 2005. Beryl made landfall in Texas as a Category 1 storm, but don’t let the reduced wind speeds fool you: The storm caused significant flooding across Texas and Louisiana.

“The impactful and deadly 2024 hurricane season started off intensely, then relaxed a bit before roaring back,” said Matthew Rosencrans, the lead hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, in an administration release. “Several possible factors contributed to the peak season lull in the Atlantic region. The particularly intense winds and rains over Western Africa created an environment that was less hospitable for storm development.”

Hurricane Helene: Flooding in Appalachia, deadliness, and atmospheric shockwaves

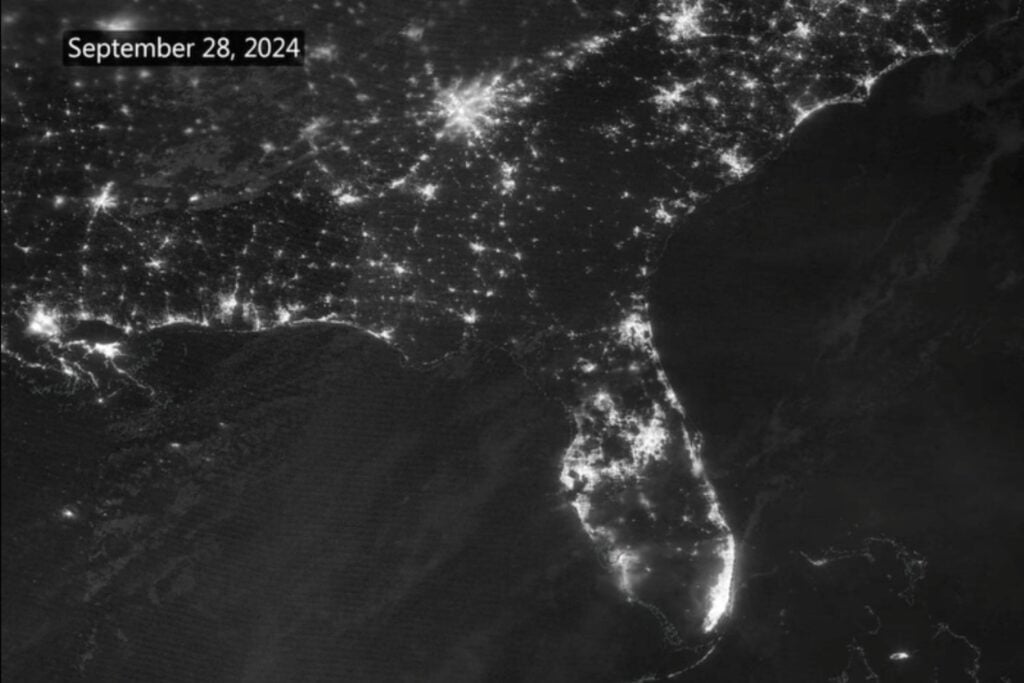

Two months ago, Florida was hit by back-to-back hurricanes in a fortnight. The first of the two was Hurricane Helene, which made landfall on Florida’s Big Bend as a Category 4 storm with wind speeds over more than 140 miles per hour (225 kilometers per hour). Over roughly 18 hours, Helene made its way from Florida up to Tennessee, causing storm surge on the coast, and tornadoes and flooding farther inland. Dramatic satellite imagery of Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas revealed the extent of the storm’s wrath, from power outages to sediment kicked up from the Gulf of Mexico’s seafloor.

Images on the ground conveyed the pain wrought by Helene, including destroyed houses and flooded city centers. But satellite imagery revealed the scale of the devastation, which stretched across the southeastern United States. NOAA data revealed last month that Helene’s reach extended into the upper atmosphere, where the hurricane generated shockwaves (also called gravity waves) up in the mesosphere.

According to the NOAA release, preliminary data suggests that Hurricane Helene is the deadliest hurricane in the continental U.S. since Hurricane Katrina. Helene directly caused more than 150 deaths, most of which were in the Carolinas.

Hurricane Milton’s eye-popping intensification

Hurricane Milton intensified from a Category 1 system into a Category 5 storm in about seven hours, a staggering pace. Milton’s rapid intensification was attributed to several factors, but chief among them was warm ocean temperatures. Atlantic and gulf hurricanes tend to form when the ocean’s surface is 82 degrees Fahrenheit (27.8 degrees Celsius) or higher; in early October, Milton was fueled by surface temperatures exceeding 85 degrees F.

The storm killed up to 25 people. According to the Palm Beach Post, Milton’s fierce winds tattered the dome of Tropicana Field, the current home of the Tampa Bay Rays, caused a crane collapse in downtown St. Petersburg, and about 3.4 million people lost power as a result of the storm.

Hurricane Milton also produced a lot of twisters—violently rotating columns of air that extend down from thunderstorms to the ground. Twisters are fairly common on the edges of hurricanes, but according to one expert, Milton’s timing and direction created “near-perfect” conditions for tornado formation. Milton generated at least three dozen tornadoes across the Sunshine State before it made landfall. When Milton finally arrived on land, it dumped months’ worth of rain on the state in just a day—and NOAA’s new lightning satellite captured the storm’s intensity from orbit.

The season petered out after multi-million-dollar wallops

The total cost of damages and economic losses due to the 2024 hurricane season could exceed $500 billion, according to AccuWeather. The company determined Hurricane Helene was the costliest storm of the year, with total damages clocking in around $225 billion to $250 billion.

The 2024 season ultimately yielded 18 named storms, eleven of which were hurricanes and five of which became major hurricanes (storms with sustained winds of over 111 mph, or 179 kmph). The most storms on record (seven) formed in the Atlantic since September 25, another indicator that the season was still more active than usual, though it didn’t have as many named storms as last year.

Hurricane season won’t return until late June, but keep an eye out for forecasts early next year. They will give an early glimpse at how the 2025 season will shape up.

Read the full article here