Around 66 million years ago, a massive asteroid stretching 6 miles (10 kilometers) across struck Earth, ending the reign of the dinosaurs. Today, the probability of an asteroid that size wiping out humanity is quite low, but there are thousands of smaller space rocks lurking around Earth’s orbit capable of destroying entire cities, and those have a higher chance of crashing into our planet. The problem is, we don’t really have a viable plan of defense.

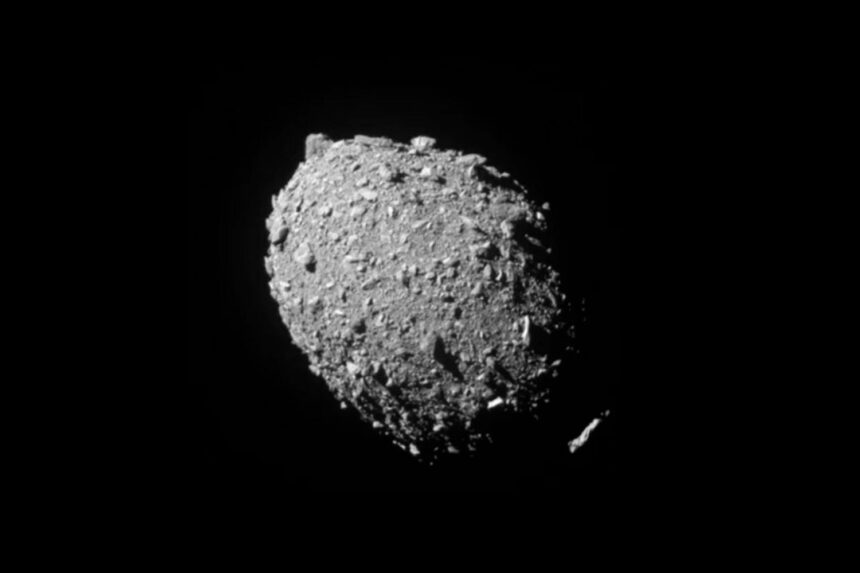

In September 2022, a NASA spacecraft crashed into a city-killer-sized asteroid to slightly nudge it off its orbital course and test kinetic impact as a means of planetary defense should an asteroid be headed our way. NASA’s DART mission (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) was a success, proving that we may stand a chance against the flying piles of rubble.

In his new book, How to Kill An Asteroid, award-winning science journalist Robin Andrews offers a rare personal look at the development of the mission, the team that made it happen, and what it was like to be inside the mission control room when the asteroid got smacked. The book leans into the sci-fi fantasy aspect of the mission, detailing all the cool science while still delivering drama, humor, and a great group of characters.

Gizmodo: What got you interested in the DART mission?

Robin Andrews: I’m a volcanologist by training. So, I love writing about volcanoes, earthquakes, or anything that’s sort of dramatic, Earth-shifting stuff that makes you feel small—stuff that really kind of affects us in a more literal way. There’s nothing really more literal than something in the solar system coming to crash into us.

I covered DART’s launch, and I was surprised that more people, even within NASA, weren’t making a bigger deal with it, because it felt so pop culture. I grew up watching Armageddon and Deep Impact as a nerdy kid, and I knew a lot of it was a bit silly, but like, the idea of asteroids and things crashing into the planet felt so real. It’s a real danger, but it felt really weird that NASA wasn’t making a much bigger deal out of it.

It just struck me as weird that that kind of subject of planetary defense hadn’t been covered that much, so I’d felt really stupid if I didn’t pitch it.

Gizmodo: Did you plan on writing a book about the DART mission from the start?

Andrews: It was through covering it. I think the thing that really fascinated me in particular is that most spacecraft NASA and others build, they want to live for as long as possible. They have this eight minutes of terror on Mars when [the rovers] land and there are obituaries for spacecraft that die. But the point of this spacecraft was to die; if it missed and it kept living, then they had messed up. So there was this weird inversion of what people expect and it just felt very dramatic.

Gizmodo: There’s so much humor in your book. Did that just come naturally?

Andrews: Sometimes when you speak to scientists for long enough, they sort of get more comfortable and I just got the sense that most of them are quite goofy. I think I really connect with people like that anyway, and it doesn’t matter who they are, whether they’re a journalist or a scientist. If they don’t take themselves that seriously, I think I always get on with them. So it felt a lot easier to slip into the goofiness once you saw a sign of it.

Gizmodo: How did this real-life NASA mission compare to some of the movies that portray asteroid collisions?

Andrews: It was super surreal, and it felt more sci-fi to some extent rather than just straight science. I love science, obviously—I’m a big massive geek. But it struck me how the science in the mission was relatively straightforward to just allow them to do something relatively simple, as in punch an asteroid.

Gizmodo: What was it like to be inside mission control during that time?

Andrews: It was amazing. Honestly, I had a feeling we’d hit it, but having spoken to them throughout and finding out that, actually, there were points behind the scenes where they were not as confident as the official statements were portraying, there were malfunctions on the spacecraft and things like that.

No matter how sure someone says that they’re gonna do something, if someone’s never done this before, you think anything could happen at this point. And it was properly exhilarating. I’m not massively into sports, but the buzz in that room was better than any sports game anyone has invited me to. There was so much riding on this one thing, and all the engineers looked so pale, white, nervous. You couldn’t make it up how dramatic it was—they only had one shot to do this.

You’re meant to be objective to these things but you couldn’t help but get wrapped up in it a bit. I’ve never seen people jumping up and down and screaming so much.

Gizmodo: What were the most challenging parts of the mission?

Andrews: I think just getting the mission off the ground. It’s amazing that they even managed to fund this mission. It might be like the space debris problem; you just imagine that an astronaut is gonna get killed by a bit of flying debris or a piece of a rocket is gonna land on someone’s house, and maybe then someone will do something.

It struck me as very strange that planetary defense was considered the same as planetary science for quite a long time. I can’t remember who said it, but someone was like, “Oh, planetary science is great but it’s pointless if we’re all dead.”

Gizmodo: And you’re not just talking about asteroids that would wipe out the entire planet, but smaller asteroids that can still cause significant damage?

Andrews: Yeah, I think that was another thing that made me really want to write this book. There’s so much written, fiction and non-fiction, about the planet killers, but these city killers—they come out of nowhere and cause damage to a random spot on Earth. As someone who wrote about volcanoes for so long, you can never stop those from erupting but you can just knock [asteroids] away.

Gizmodo: Who do you hope reads this book?

Andrews: There’s a time for popular science to really get into the nitty gritty of the science and those books are great as well. But I have this feeling that there are a lot of popular science books that end with a message of, “well, we’re all screwed, I guess,” which I understand. It’s important to underscore that. But [DART] is such a realistic, optimistic thing, and because the characters are so kooky and the whole idea of the mission is so pop culture, I just want it to reach younger readers. I hope it convinces them that science is cool. It’s nice to have a feel-good story for once.

Read the full article here