Mast cells are part of our immune system, protecting our body from viruses, bacteria, and even harmful substances released by snake and insect bites. When alerted to the presence of such invaders, mast cells can create mucus, trigger swelling and itching, and make muscles contract in our airways, stomach, and intestines. While these symptoms allow the body to destroy or expel invaders, oversensitive mast cells cause allergic reactions, including life-threatening and hard-to-treat conditions.

As detailed in a study published Monday in the journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, researchers have developed a compound that blocks mast cells from triggering particularly hard-to-treat and sometimes life-threatening reactions. These include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), asthma, chronic itching, and migraines. Traditionally considered pseudo-allergic reactions, these conditions have more recently been classified as a type of allergy, according to the researchers. The compound seems to greatly reduce symptoms, and as a consequence, lower fatality risk.

“We thus see this as an extremely promising substance,” Christa Müller, a co-author of the study who researches medicinal chemistry of membrane proteins at the University of Bonn, said in a university statement.

Unlike some allergic reactions, in which immune cells called antibodies alert mast cells to the presence of invaders, these hard-to-treat conditions occur when mast cells are triggered through direct activation not involving antibodies. This triggers reactions “of a specific nature that have been difficult to treat, and remain so to this day,” Müller explained.

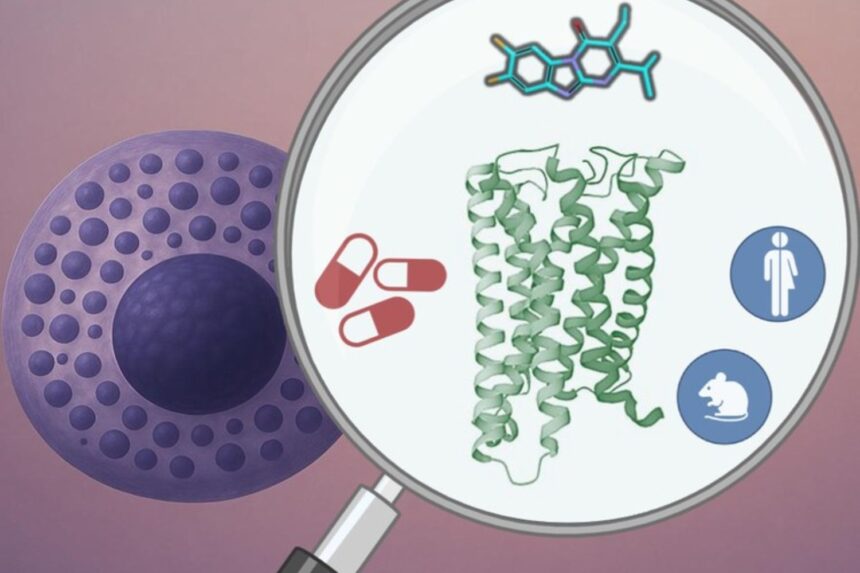

15 years ago, Müller and colleagues identified a receptor named MRGPRX2 in the mast cells’ membrane that “switches on” these sorts of reactions when certain molecules attach to it. “To prevent this reaction, the switch would have to be blocked somehow,” Müller continued. “The question was: how?”

To address this, the team tested promising compounds from a collection of 40,000 previously gathered by Müller’s department. “We used cells that light up when MRGPRX2 is activated, so we could then test whether the substances effectively block activation of the receptor, switching off the light signal,” explained Ghazl Al Hamwi, Müller’s doctoral student and first author of the study. In this way, the team discovered a molecule that can attach to the receptor and block it, effectively switching it off.

They used that molecule to develop a substance that still works in very low doses, and proved its efficacy at eliminating life-threatening allergic reactions in lab mice and blocking the MRGPRX2 receptor on isolated human mast cells. They also claimed the molecule only blocks the intended receptor, which avoids the risk of side effects.

While Al Hamwi, Müller, and their colleagues have since improved the substance’s efficacy and duration, more animal and eventually human trials will have to take place before it can be approved and commercialized as a drug. Nevertheless, it holds potentially life-saving implications for patients with some inflammatory conditions and those at risk of anaphylactic shock.

Read the full article here