Time doesn’t heal all wounds. If you’re an injured comb jellyfish, you might just need another of your species to meld with.

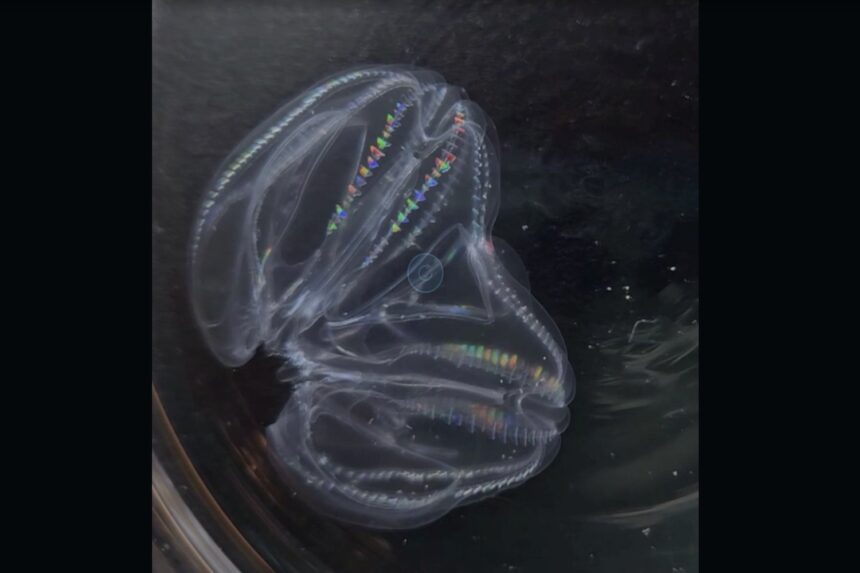

That’s what biologists at the University of Chicago’s Marine Biological Laboratory found when they were examining samples of a species called Mnemiopsis leidyi, also known as the warty comb jelly. Native to the western Atlantic, these jellyfish have a bizarre ability to fuse together after being injured, merging not only their outer tissues but also their nervous and digestive systems. The findings could have huge ramifications for the study of human regeneration.

The discovery was spurred by a random observation. A day after collecting some of the comb jellyfish from the wild, the researchers noticed that one of them had weird characteristics. These types of comb jellyfish normally have one apical organ, a sensory organ possessed by many invertebrates, but this specimen had two. It also had two aboral ends: In other words, it had two butts, which, again, is odd.

The biologists theorized that the jellyfish (singular) had previously been jellyfish (plural), and had fused together as a way to survive injuries. To satisfy their curiosity, they partially amputated lobes from other jellyfish and placed them together into a tank. As they reported in Current Biology, in nine cases out of 10, the pairs of comb jellyfish combined into a single entity. In all nine of those cases, the fused animals survived for three full weeks in their holding tanks. As three weeks was the duration of the experiment, it’s possible they could survive even longer after shmushing themselves together.

The process was a quick one. After just a single hour, the movement of grafted lobes became synchronized. An hour after that, the overall movement of the combined creature’s lobes were 95% synced up. After just one night, the boundary between the combined jellyfish had become “continuous,” the biologists wrote, with the outermost layers of tissue looking “seamless.” Even the nervous systems showed signs of gelling together. When the biologists poked a lobe on what had been one jellyfish, it caused a startled response in a lobe that belonged to the other.

“We were astonished to observe that mechanical stimulation applied to one side of the fused ctenophore resulted in a synchronized muscle contraction on the other side,” said Kei Jokura, a postdoctoral researcher who worked on the study, in a statement.

Even the digestive system acted as one. In a video of one of their experiments, one side of a fused jellyfish can be seen digesting a brine shrimp that had been injected with a fluorescent substance. As the jellyfish began digesting it, fluorescent particles can be seen flowing into the lobe of its attached compatriot, which pooped out some waste.

“The transport of digestive particles across the fused canals suggests that such systems are functionally coupled and not just physically connected,” the biologists wrote. However, the fact that only one side expelled waste may actually indicate the two jellyfish don’t truly become a single animal. “The lack of synchronized excretion suggests that the transient nature of the anus and its ultradian rhythm remain independently controlled in the fused individuals,” the scientists added.

There’s still much to learn about how the fused jellyfish function, and why this weird behavior helps them survive. In the paper, the scientists said it’s not clear how the nervous systems are able to join together, something they hope to learn more about with further experimentation.

The discovery could go beyond describing a novel survival mechanism. Jokura said it appears the jellyfish lack a system for allorecognition, or the ability to recognize if cells belong to the self, or to others. Allorecognition is a key component to medical procedures like organ transplants, so these weird sea creatures, who might be big Spice Girls fans, could hold the key to advances in immune system and regeneration therapies.

Read the full article here