What follows in the wake of tropical cyclones—strong, rotating storms that start above tropical oceans? Many people likely imagine destruction, if not even death. Hurricane Katrina, for example, was a tropical cyclone. New research, however, highlights a lesser-known impact on oceans.

A team of researchers has used computer models to simulate tropical cyclones at high resolutions and investigate their effect on the carbon exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere. Their results carry implications for understanding how global warming could impact these storms.

High-resolution computer models

“Earth system models typically work with spatial resolution of 100 to 200 km [62 to 224 miles]. This is too coarse for the representation of small-scale mechanisms and extreme events, such as intense tropical cyclones (e.g. hurricanes),” the researchers wrote in a study published last week in the journal PNAS. “We present a [kilometer] scale global Earth system model simulation that resolves interactions between extremely intense cyclones and the ocean carbon cycle with unprecedentedly high resolution (5 km [2.7 miles] ocean and atmosphere).”

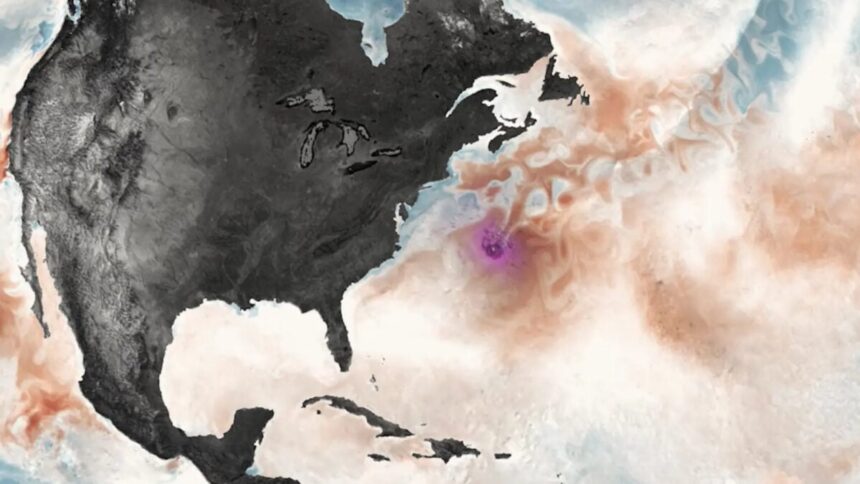

The team studied its one-year simulation’s two strongest tropical cyclones in the western North Atlantic, both with wind speeds of over 124 miles per hour (over 200 kilometers per hour), and the changes that occurred in their wake. Both were hurricanes—a tropical storm is considered such if its surface wind speeds reach 73.8 miles per hour (118.8 km/h) or faster, according to the researchers. The second storm formed around a week after the first.

By churning the ocean’s surface waters, tropical cyclones mix water masses and cause the ocean to exchange heat and carbon with the atmosphere. The simulations revealed that the storms caused the ocean to release carbon dioxide immediately into the atmosphere, an event 20 to 40 times stronger than what would have taken place in normal weather conditions. The cyclones also lowered ocean surface temperatures, raising the water’s absorption of carbon dioxide for a number of weeks in the wake of the storms. Taken together, the ultimate result was a small increase in absorption.

“It was exciting to learn that as a consequence, the hurricanes also increased the amount of organic carbon sinking down in the ocean, contributing to the long-term storage of carbon in deeper ocean layers,” Tatiana Ilyina, a co-author of the study and a group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, said in a Max Planck statement.

Extra phytoplankton

What’s more, the researchers found that the hurricanes’ water-mixing effect pulled nutrients up to the surface, with the simulation showing phytoplankton consequently growing tenfold. This bloom endured for a few weeks after the hurricanes passed and spread throughout significant areas of the western North Atlantic on local currents, which the hurricanes had, in part, intensified.

While researchers had previously observed some of these dynamics, “this simulation allows us to study them in detail and link them to the global scale, which is important if we want to understand how tropical cyclones might respond to and impact our climate under global warming,” said David Nielsen, first author of the study and a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology.

Moving forward, Nielsen and his colleagues will also investigate other processes on the kilometer scale and the consequences for the ocean carbon cycle, including in polar regions.

Read the full article here