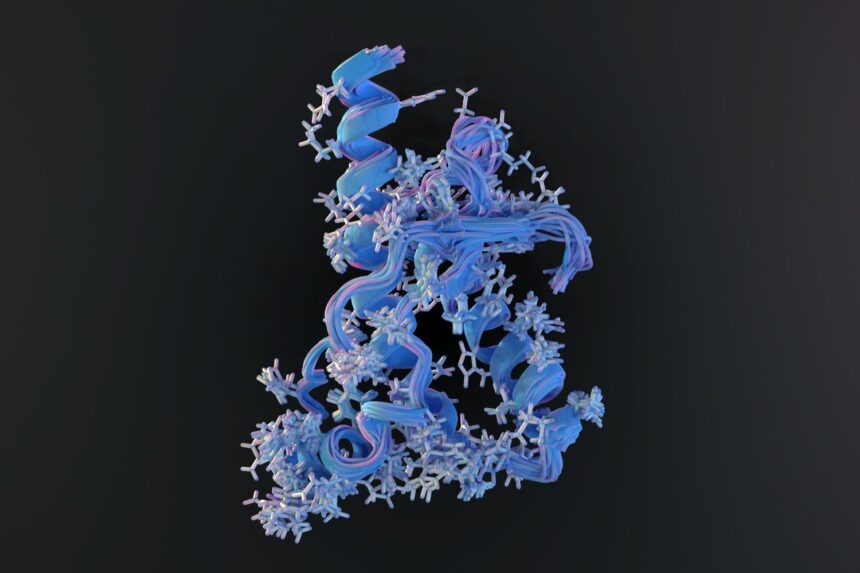

A tiny protein is responsible for one of the most horrific ways to die: the prion, a germ unlike any other. Despite not having any genetic signature of life—like bacteria, fungi, and even viruses do—these proteins can fold into a malignant, zombie-like form that converts normal prions into a copy of themselves, which eventually destroys the brain from the inside out. In a new book The Power of Prions, author and scientist Michel Brahic provides a close-up view of these mysterious proteins.

Brahic is a French microbiologist who’s been connected to the world of prions for decades. Though he personally focused on unraveling the viral triggers of brain diseases, he was an early colleague of Stanley Prusiner, one of the eventual Nobel Prize-winning discoverers of prions. Later in his career, Brahic’s research veered toward finding how other brain proteins may cause diseases like Parkinson’s in much the same way as classic prions cause ailments like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) or mad cow disease.

In his new book, Brahic details how the exponential growth of prions can wreak havoc throughout the brain, causing universally fatal but thankfully rare diseases like kuru and CJD in humans, chronic wasting disease in deer, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cows, better known as mad cow. Before diving in, he provides a clear, straightforward overview of how the nervous system and proteins function. He also discusses the research showing how prion-like proteins could have a role in diseases like Alzheimer’s and type 2 diabetes, and why the chaotic shapeshifting of these proteins may actually be crucial to our very existence.

Gizmodo spoke to Brahic about why he decided to delve deep into a book about prions, how prions might inform our understanding of other, much more common disorders, and the biggest riddles left to solve about these “molecular devils.” The following conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and grammar.

Ed Cara, Gizmodo: You’ve spent your career studying how viruses and eventually prions can harm the brain. What made you want to write a book about these mysterious proteins for a general audience?

Michel Brahic: Not everybody, even some physicians, are aware that prions are implicated in some very common diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and some others. There is the prion protein, which is the agent of frightful but rare diseases like mad cow, etc. But there are also different proteins that can behave in the same way as prions that might have a causal role in these other diseases. That’s not widely known, and I want to make that known for two important reasons.

The first is that it could create anxiety and misunderstanding if people start to think that Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, etc are contagious [some forms of prion disease can be transmitted between humans and from animals to humans, such as mad cow]. I wanted a book that says, “No, they are not infectious.” They have some common ways of behavior at a cellular level, but the big difference is they don’t spread from human to human, unless maybe through some surgical contamination, but even that is not clearly established.

The other aspect is that now that we know these prion-like proteins are involved in common diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, it opens the door for a new way of thinking. Because what’s important is that prion proteins can explain how such diseases spread within the brain, from cell to cell, from neuron to neuron, essentially. And if we understand the mechanism of the spread of these molecular devils, we can think about how to interfere with that, blocking that spread.

Gizmodo: You detail many of the things we’ve learned about prions since their formal discovery in the 1980s, as well as the basic neurology that made these discoveries possible. But what are some of the biggest questions still left to answer about prion and prion-like proteins?

Brahic: One of the main questions that we haven’t solved is, for example, in Alzheimer’s: How do they kill the neurons? We truly don’t have a good understanding of the toxicity of those prions, and obviously understanding that is very important if you want to devise treatments.

Of course, there’s work going on in that field. For example, prions may interfere with the function of some organelles called mitochondria, which provide the energy to the cell, but this is still not completely clear. There are other possibilities like a sort of starvation. Once a protein turns into a prion, most of the same proteins which are in the neuron are going to turn into prions also, and that process may deprive a neuron of some important components which are now part of this prion mass and which are not available for performing their normal function. So there are several ways of thinking about how they can be toxic for the cells, but it hasn’t been really completely clarified, and we need more research in that direction.

Another aspect is that beside Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, how many more diseases are involved with this prion protein? There is a group of diseases in humans called amyloidosis, which are diseases where proteins aggregate [clump together into a mass], and it’s also a fact that a key property of prion proteins is that they aggregate. Not all the amyloid diseases are due to prion-like proteins, but we may have more that haven’t yet been considered for that possibility, including diseases outside the brain. And then if they are, then we are back to the same idea of trying to prevent them by preventing spread, by preventing toxicity, etc. So I think that’s another direction that needs to be explored.

Gizmodo: Prions are most well-known for being terrifying, practically impossible to stop germs. But you also take some time to talk about the ways that prions or prion-like proteins are crucial, perhaps fundamentally so, to people and other forms of life.

Brahic: Prions were discovered because of kuru, because of the exotic diseases they cause. Nobody at the time when those discoveries were made would have thought that by discovering prions, we would open up a new theory on the origin of life on the planet [some scientists have argued that prion-like proteins were part of the earliest stages of evolution on Earth, even before the emergence of DNA and RNA]. So what I want to emphasize here is the importance of looking at strange things that may not be obviously very important to everybody’s lives, but that may lead to some fundamental discovery, of which prions are a good example of.

We now know that there are prion proteins which are essential for human functioning. But the problem is that we’ve just barely scratched the surface—there is a ton of stuff we don’t yet know about how these proteins are important to our cells in general.

Gizmodo: I think one reason why prions remain so bleakly fascinating to people is that classic prion diseases like CJD or mad cow are 100% fatal once symptoms emerge. Will we ever be able to someday defeat prions as we can viruses or bacteria?

Brahic: There are several labs that are looking at the very basic folding problem, the misfolding problem of prion proteins, and trying to screen for existing compounds or to design some compounds that can block that process. Of course, you need to find a drug that can enter the cell, that can go all the way to the brain, if it’s a brain disease, but that is not toxic. So there is some unusual pharmacology that has to go into that, which is not done yet, but I do see hope in that direction. And again, if we can understand how they kill the cells, that we also can hope to interfere, maybe not just with the agent, but with their toxicity, and try to protect the cells from being sensitive to the presence of the prion.

So there are many ideas which I think should yield promise and will lead to some new classes of drugs.

Gizmodo: What do you hope people most take away from this book?

Brahic: I think there’s a lot for the reader who’s just intrigued about seeing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s on the cover to discover—not just about prions, but what even a protein is, how it folds, and all of that.

I also think that science is not always communicated to the lay public in a way that explains how the results are obtained. How are they significant? What’s the probability of something to be proven correct after further investigation? We mainly hear in the press about big things, big news, which are often described as a breakthrough without really explaining how it happened. And sometimes there are some disappointments after those claims which have led to—as we all know—to misunderstandings between the public and the medical profession about things like vaccines. Vaccine denial is, to me, a very serious problem causing a lot of harm.

So I also wanted to go into the ways that results are obtained in the lab, in practice, and to try to give a more realistic impression to the reader of how science is being done, and how sometimes we are not sure, that sometimes we can make mistakes, etc. And that’s all in the goal of trying to improve the relationship between

scientists, science in general, medical science in particular, and some part of the public and the patients who tend to mistrust the way it’s communicated.

And I don’t want to criticize science journalists too much, but I think journalists should also pay some more attention to describing how science is being done, more than just talking about big results and not providing much comment about it [this reporter wholly agrees, by the way!].

The Power of Prions: The Strange and Essential Proteins That Can Cause Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Other Diseases will be published October 29 by Princeton University Press.

Read the full article here