Germs might be even worse for us than we thought. New research suggests that certain infections could be a contributing factor to heart attacks.

Scientists in Finland and the UK conducted the study, which examined arterial plaques taken from people who died from heart disease and others. They found these plaques often contained a dormant layer of bacterial biofilm; they also found evidence that bacteria released from this biofilm can then trigger heart attacks. Though not yet definitive, the study may someday point to another way we can prevent or treat heart attacks, the researchers say.

“This finding adds to the current conception of the pathogenesis of [heart attacks],” the researchers wrote in their paper, published last month in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

A potential double whammy of infection

Many studies have suggested that some infections can make us more vulnerable to a heart attack, also known as a myocardial infarction. But according to the study researchers, it’s been difficult to pin down the exact mechanisms involved in this potential chain of events.

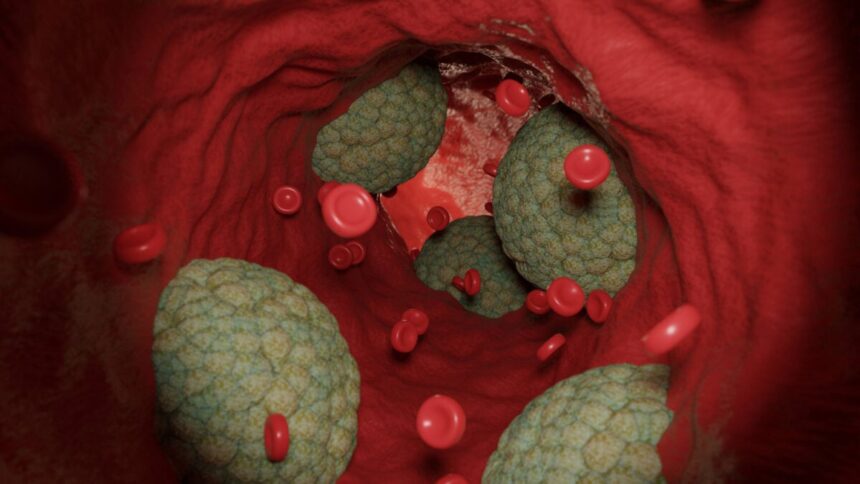

The researchers studied arterial plaques—the deposits of cholesterol and other debris that can build up along our arteries—collected from people who suddenly died as well as from patients who had their plaque surgically removed. Using various methods, including genetic sequencing, they identified several groups of bacteria normally found in our mouths lodged within these plaques.

These bacteria had formed biofilms, hardy and sticky layers of bacterial colonies. The bacteria inside a biofilm are much better at fending off the immune system and antibiotics than they would be individually.

The researchers found that the biofilms stuck deep inside plaques didn’t trigger the immune system. But some plaques contained bacteria shaken loose from the biofilm, and these bacteria did seem to spark an immune response and resulting inflammation. What’s more, the presence of these released bacteria also appeared to be associated with ruptured plaques and heart attacks.

“Bacterial involvement in coronary artery disease has long been suspected, but direct and convincing evidence has been lacking. Our study demonstrated the presence of genetic material—DNA—from several oral bacteria inside atherosclerotic plaques,” said lead author Pekka Karhunen, a researcher at Tampere University in Finland, in a statement from the university.

The authors say that it may take a sort of double whammy for these bacteria to stir up heart trouble. Typically, the biofilm inside these plaques remains hidden and dormant. But when something else activates the bacteria—such as a secondary viral infection—the bacteria grow and set off the immune system, causing inflammation that breaks open the plaque. The broken-off plaque can then produce clots that block the artery’s blood flow, causing a heart attack.

Unanswered questions and new leads

The team’s results will have to be validated by additional studies, ideally from other research teams. But if confirmed, their work could certainly help us better combat heart disease.

It’s possible, the researchers say, that giving a short course of antibiotics to people whose heart attacks are caused by these bacteria could improve their outcomes, for instance. Someday, we might even be able to reliably prevent heart attacks using vaccines against these bacteria or common secondary infectious triggers.

Notably, several studies have already suggested people vaccinated against flu, covid-19, and shingles have a lower risk of heart disease.

Read the full article here