Millions of years before the dinosaurs came along, there was a creature scurrying around that some people might find far more terrifying than any tyrannosaur. Picture a millipede, but it weighs over 100 pounds (45 kilograms) and its body is the length of a car.

These Lovecraftian nightmares were called Arthropleura, and they are the largest known species of arthropods to have ever existed. Thankfully for those who get the willies from wriggly animals, the 8.5-foot-long (2.6 meters) creatures, which first appeared 346 million years ago, disappeared around 50 million years after that.

The critters left behind a mystery for modern paleobiologists to ponder over: Just how closely related were they to their far, far smaller modern counterparts? While the ancient giants are commonly classified as myriapods, a group of animals that’s dominated in the modern day by millipedes and centipedes, it wasn’t clear where, exactly, Arthropleura belonged on the family tree. Scientists from several French universities may have found the answer by looking the bizarre critters straight in the face.

That was actually a fairly difficult thing to do. Although Arthropleura was first discovered in 1854, most of the fossils found have been fragmentary—and none have included a complete head. The record has been so incomplete, and the creatures so alien, that some paleobiologists mistook a neck-like part called the collum for the head. There’s been no evidence for what Arthropleura’s eyes, antennae, and mouth may have actually looked like, so it’s been hard for scientists to tell if there’s a family resemblance with the multi-legged organisms you can find in most gardens.

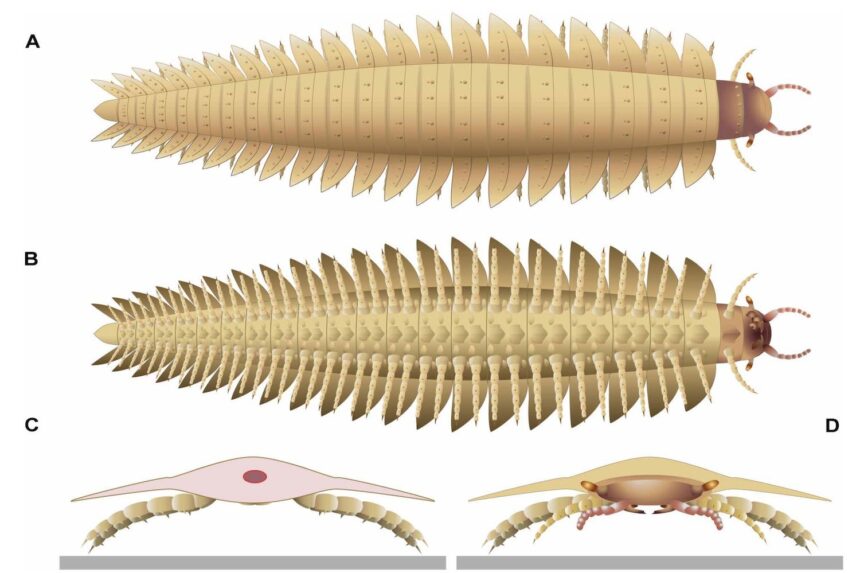

To solve that problem, the paleobiologists, led by Mickaël Lhéritier of the Universite Clauder Bernard, scanned the remains of several particularly well-preserved juveniles, and used tomographic imaging techniques to recreate their mugs. As Lhéritier and his colleagues described in the journal Science Advances, the ancient arthropods did pass along some of their facial features to their distant modern day relatives.

Like millipedes, the scans showed Arthropleura had seven-segmented antennae, and a modified collum behind their heads. Arthropleura also had some features in common with centipedes, such as fully encapsulated mandibles, and a pair of leg-like jaw structures called maxillae. While centipedes and millipedes are both myriapods, their exact relationship to each other has been a subject of some controversy among myriapod enthusiasts. The new findings suggest the two species should be grouped together, due to a common heritage that makes them more closely related with each other than they are to other myriapods, such pauropods.

With a more complete idea of what Arthropleura looked like, the paleobiologists said there were some inferences that could be made about how they behaved. Their diet, the scientists wrote, likely consisted of already dead animals they could scavenge.

While the study offers the most fully realized view of the extinct arthropods to date, James Lamsdell, an associate professor of paleobiology at West Virginia University, wrote an accompanying article stating that there’s still much we don’t know.

“Without direct evidence from digestive tracts, it is still unclear exactly what Arthropleura ate,” he wrote. “The respiratory organs also remain unknown, leaving the possibility that Arthropleura was aquatic.”

Lamsdell said it also can’t be ruled out that Arthropleura spent different stages of its life in different environments. So there you have it: millions of years ago, creepy crawlies that were about as long as an alligator roamed the land, and possibly water, snatching up bites of dead animals. Next time you see a millipede running around your floor, take a second to be grateful for its diminutive size before you decide to squish it.

Read the full article here