Rising sea levels cause visible damage to coastal communities—but we should also be worried about what’s happening beneath our line of sight, as upsetting new research suggests.

New research from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) suggests that that seawater will contaminate underground freshwater in roughly 75 percent of the world’s coastal areas by the end of the century. Their findings, published late last month in Geophysical Research Letters, highlight how rising sea levels and declining rainfall contribute to saltwater intrusion.

Underground fresh water and the ocean’s saltwater maintain a unique equilibrium beneath coastlines. The equilibrium is maintained by the ocean’s inland pressure as well as by rainfall, which replenishes fresh water aquifers (underground layers of earth that store water). While there’s some overlap between the freshwater and saltwater in what’s known as the transition zone, the balance normally keeps each body of water on its own side.

Climate change, however, is giving salt water an advantage in the form of two environmental changes: rising sea level, and diminishing rainfall resulting from global warming. Less rain means aquifers aren’t fully replenished, weakening their ability to counter the saltwater advance, called saltwater intrusion, that comes with rising sea levels.

Saltwater intrusion is exactly what it sounds like: when saltwater intrudes inland further than expected, often jeopardizing freshwater supplies such as aquifers.

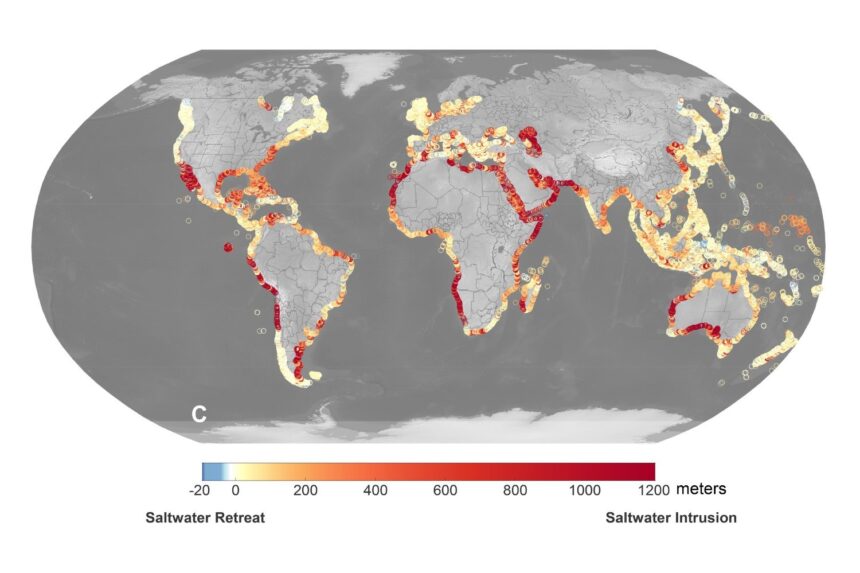

To study the future reach of saltwater intrusion, JPL and DOD researchers analyzed how rising sea levels and diminishing groundwater replenishment will impact over 60,000 coastal watersheds (areas that drain water from features such as rivers and streams into a common body of water) worldwide by 2100.

As detailed in the study, the researchers concluded that by the end of the century, 77% of the studied coastal watersheds will be impacted by saltwater intrusion because of the two aforementioned environmental factors. That’s over three of every four evaluated coastal regions.

The researchers also considered each factor individually. For example, rising sea levels alone will move saltwater inland in 82% of the coastal watersheds considered in the study, specifically pushing the freshwater-saltwater transition zone back by up to 656 feet (200 meters) by 2100. Low-lying regions such as southeast Asia, the Gulf of Mexico coast, and parts of the US east coast are especially at risk of this phenomenon.

On the other hand, a slower replenishment of underground freshwater will allow saltwater intrusion in just 45% of the studied watersheds, but will push the transition zone inland as far as three-quarters of a mile (about 1,200 meters). Areas including the Arabian Peninsula, Western Australia, and Mexico’s Baja California peninsula will be vulnerable to this occurrence. However, the researchers also noted that groundwater replenishment will actually increase in 42% of the remaining coastal watersheds, in some cases even prevailing over saltwater intrusion.

“Depending on where you are and which one dominates, your management implications might change,” Kyra Adams of JPL and a co-writer of the study said in a JPL statement, referencing rising sea levels and weakened aquifers.

Sea level rise will likely influence the impact of saltwater intrusion on a global scale, whereas groundwater replenishment will indicate the depth of local saltwater intrusion. The two factors are, however, closely linked.

“With saltwater intrusion, we’re seeing that sea level rise is raising the baseline risk for changes in groundwater recharge to become a serious factor,” said Ben Hamlington of JPL, who also co-led the study.

Global climate approaches that take into account local climate impact, such as this study, are essential for countries that don’t have enough resources to conduct such research independently, the team highlighted, and “those that have the fewest resources are the ones most affected by sea level rise and climate change,” Hamlington added.

The end of the century might seem like a long way, but if nations and industries need to mobilize in response to these predictions, 2100 will be upon us sooner than we think.

Read the full article here