In 1960, a villager found something terrifyingly creepy in Greece’s Petralona cave—a humanoid cranium with a protrusion on its forehead, fused to the cave wall. Since then, researchers have been trying to date the strange specimen and understand how it got there, but these efforts so far have yielded only a frustratingly broad age range of between around 170,000 and 700,000 years.

The skull’s ambiguous stratigraphic position is also less than helpful. So a team of researchers took a slightly different approach, dating the skull’s unicorn-like calcite protrusion. In turn, they’ve narrowed the potential age of the specimen and potentially shed light on a mysterious ancient hominid.

The study was published last month in the Journal of Human Evolution.

A mysterious species

“I saw the skull in 1971 for the first time when I was going around Europe for my PhD trip,” Chris Stringer, an anthropologist at University College London and study co-author, told Gizmodo.

“Then it was said to be a Homo erectus or a Neanderthal, and for me it was neither of those. So that was the beginning of my idea that there was a different kind of human around in Europe.”

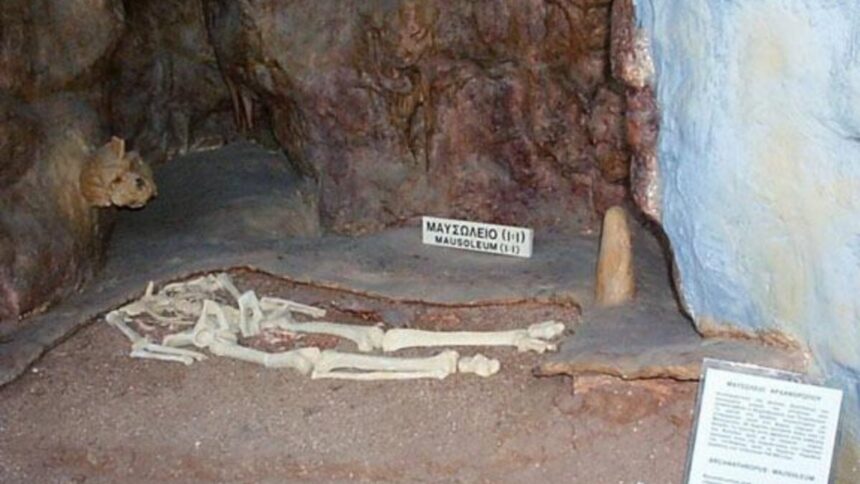

Stringer and his team performed U-series dating—a technique for dating geological formations based on the radioactive decay of certain forms of uranium atoms—on the skull’s calcite growth. Calcite is a common mineral that often forms into stalactites and stalagmites in caves as calcium in water dripping down the cave walls reacts with carbon dioxide. In fact, the calcite on the Petralona skull is a stalagmite. Using this approach, the researchers concluded that the cranium is at least 290,000 years old.

How close this is to the skull’s actual age, however, depends on how long it was “lying around before that layer of calcite formed on it,” Stringer said. He theorizes that the calcite likely started to form soon after the skull appeared in the cave: “If that’s true, then the date we’ve got is a good date for the fossil,” Stringer said.

Better yet would be to date the skull directly—for example, via a tooth sample. But that’s something that the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, where the skull is stored in the Museum of Geology, Palaeontology and Paleoanthropology, would need to agree upon first.

A Neanderthal neighbor

Morphologically, the team agrees with the hypothesis that the Petralona skull belonged to a member of a separate and much more primitive group than both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Their new minimum age estimate bolsters the theory that this mysterious ancient group was at least contemporaneous to Neanderthals during Europe’s later Middle Pleistocene, some 430,000 to 385,000 years ago.

“My view is, and it has been since 1981, that there is this group of humans in Africa, Europe, probably in Asia, too. And the first named specimen in that group was the jawbone from Germany, found in 1907, and that was named in 1908 as Homo heidelbergensis, a new species, because it was found near Heidelberg,” Stringer explained. “And I took on that species name for the Petralona cranium, and I said, it’s probably the species heidelbergensis.”

Stringer’s hypothesis aligns with other research highlighting similarities between the Petralona skull and the Kabwe cranium from Zambia, a fossil that dates back to around 300,000 years ago and might also be the remains of an H. heidelbergensis.

Although Stringer has previously posited that that species was likely a common ancestor of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, he has changed his opinion somewhat: “I would say that heidelbergensis now is a separate branch coexisting with sapiens and Neanderthals, that goes back a long way, probably more than a million years,” he said.

Read the full article here