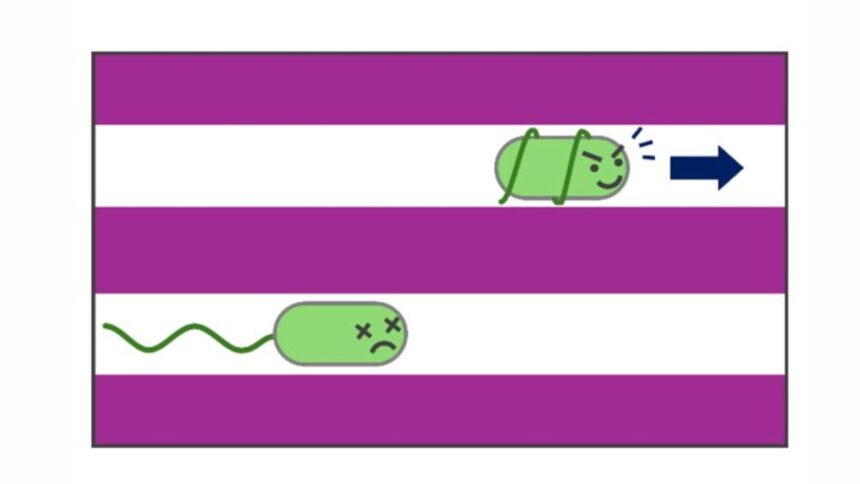

Some bacteria travel through incredibly small spaces. Researchers—and a researcher’s awesome illustration of a devilishly satisfied microbe—have revealed how the bacteria Caballeronia insecticola is able to traverse narrow passages in a bean bug’s digestive tract.

In a study published last week in Nature Communications, a team of researchers found that C. insecticola navigates through a bottleneck in the bug’s gut just 1 micrometer wide via a “flagellar wrapping” motion. In this process, the microbe wraps its flagellum—the tail-like part bacteria use to move—around itself and advances like a rotating corkscrew. The finding reveals how this species successfully moves through such a narrow passage and could also inform treatment for harmful bacteria.

‘Screw-thread’ configuration

“A few years ago, researchers noticed something unusual: C. insecticola sometimes wraps its flagella around the front of its body instead of trailing them behind like a normal swimmer,” Daisuke Nakane, a researcher at the University of Electro-Communications and co-author of the study, wrote in a Behind the Paper article for Springer Nature. “This wrapped ‘screw-thread’ configuration rotates like a miniature tunneling machine, helping the cell push forward. But was this quirky movement just a curiosity—or was it the key to conquering narrow spaces?”

According to Nakane, researchers have wondered about the species’ ability to navigate through such small spaces for quite some time. Nakane and her team placed C. insecticola in a device with channels nearly identical in width to the actual bottleneck. As you can see in the video below, the bacteria traveled smoothly through these restricted channels.

The wee beasties mostly changed their locomotion to flagellar wrapping. While around 15% of the bacteria turned to flagellar wrapping in broad chambers, 65% used it in the researchers’ tiny corridors, and it only took restricted space to trigger the change. Computer simulations revealed the secret behind the method’s success.

“In a narrow space, liquid around the cell barely moves because the walls hold it back. An extended flagellum—which normally pushes water backward—becomes almost useless,” Nakane explained. “But a wrapped flagellum creates a rotating helical surface that squeezes fluid through the tiny gap between the cell and the wall. This generates strong forward thrust, turning the bacterium into a self-propelled screw perfectly tuned for tight environments.”

An elegant rule

Nakane and her colleagues discovered that some C. insecticola relatives acted comparably. Species that can use flagellar wrapping could sustain their speed very well as they sailed along the tiny tunnels, while those incapable either greatly decelerated or completely stopped at times.

The researchers also showed that a bacterium’s wrapping ability lies in the hook, a flexible joint at the flagellum’s root that gives it more or less flexibility depending on the species. The team confirmed their theory—that C. insecticola has a flexible hook that enables flagellar wrapping—through genetic modification experiments.

When researchers replaced C. insecticola’s flexible hook with a stiffer version from another species, the microbe could no longer use flagellar wrapping and ground to a screeching halt in tight spaces. But when equipped with C. insecticola’s soft hook, the other species could—at least to some degree—engage in flagellum wrapping, allowing it to move through tighter spaces.

“Physics simulations recapitulated these results, reinforcing the simple but elegant rule: a flexible hook enables wrapping; wrapping enables tunneling; tunneling enables survival,” Nakane said. “And this wasn’t just a laboratory phenomenon. When we tested stiff-hook mutants inside real bean bugs, their ability to colonize the host plummeted. Without wrapping, they could not pass through the one-micrometer barrier. Evolution had clearly shaped the hook’s softness to help the bacteria navigate their host’s internal architecture.”

The flagellar wrapping club

Scientists observed similar movements in organisms like Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Pseudomonas—bacteria that travel through glandular ducts and mucus layers—suggesting that flagellar wrapping may be a common trait among microbes needing to traverse narrow and viscous areas.

Perhaps more excitingly, the ability to either hinder or augment this strategy could slow harmful bacteria and support beneficial ones. This clever gear switch could also inspire the configuration of nanoscale drilling systems or micro-robots.

Read the full article here