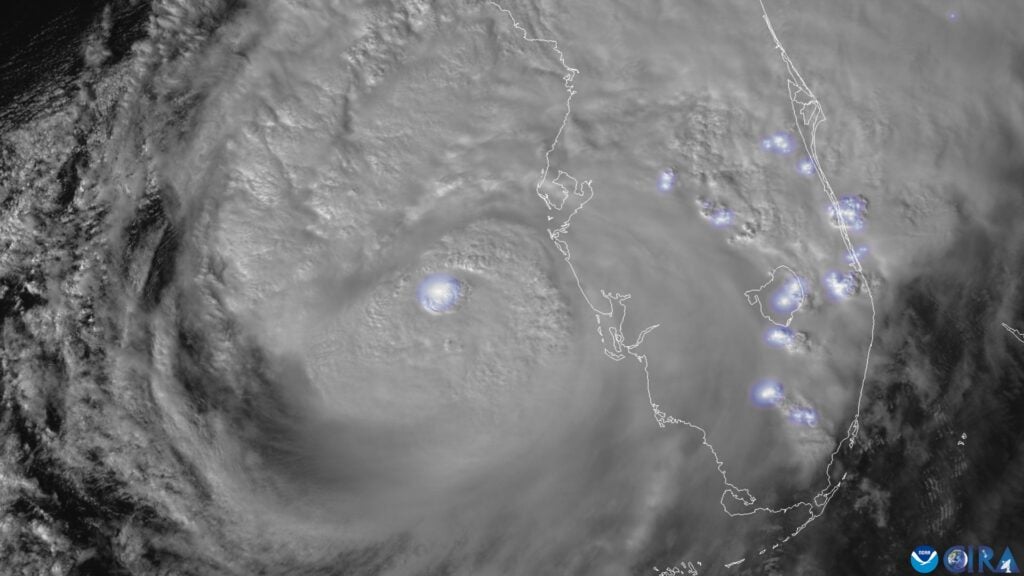

Hurricane Milton caused serious damage across central Florida yesterday, making landfall as a Category 3 storm near Sarasota that has killed at least five and left over three million people without power. But one of the most eye-catching, serious weather events associated with the storm preceded its arrival: dozens of tornadoes that cropped up across the Sunshine State yesterday afternoon.

Tornadoes are violently rotating columns of air that extend from the bottom of a thunderstorm to the ground. The weather phenomena are remarkably powerful and have the capacity to destroy buildings and hurl everything from lampposts to cars through the air like projectiles.

Tornadoes often happen at the periphery of hurricanes, but for many, the sheer number of twisters yesterday were a surreal preamble to a storm that would end up dumping months’ worth of rain over central Florida in just a day. More than 125 tornado warnings were issued by National Weather Service stations in central Florida, CNN reported, making it the most warnings ever issued in the state in one day and nearly doubling the former record of 69 warnings in a day, issued during Hurricane Irma in September 2017.

So what is the total tornado count so far, and why did Milton provide such fertile ground for the dangerous phenomenon?

Hurricane Milton caused at least three dozen tornadoes—but probably more

For tornadoes to form—whether on the Great Plains or South Carolina, as they did during Hurricane Helene last week—you need a couple of factors.

“We’re looking for two basic things to happen: You have to have thunderstorms, and you have to have the right winds,” said Rich Thompson, Chief of Forecast Operations for the Storm Prediction Center, part of the National Centers of Environmental Prediction under NOAA’s National Weather Service, in a phone call with Gizmodo.

At the Storm Prediction Center’s headquarters in Norman, Oklahoma—smack dab in tornado alley—the winds are often sufficient for tornado formation, Thompson said, but the region only gets warm and humid enough to support thunderstorms in the springtime.

In Florida it’s the opposite. The state is warm and humid all the time, but it lacks wind shear. “That’s where the hurricane comes in,” Thompson said. “You get the increases in the wind profile you wouldn’t have otherwise.”

As of 8 p.m. ET yesterday, at least 116 tornado warnings were issued and the state experienced 19 confirmed tornados, Governor Ron DeSantis said in a press conference last night—numbers which have since climbed. These tornadoes mostly occurred south of Orlando and were concentrated on the state’s Atlantic coast, especially around Port Saint Lucie, the sixth-largest city in Florida. CNN reported that the National Weather Service’s latest numbers stood at 27 tornadoes across the state, and at least four deaths associated with some of those tornadoes touching down.

“It’s hard to really say what the numbers are, but our conservative version of it right now is 38 tornadoes,” Thompson said, which is an estimate based on an initial rough count of 45 tornadoes. “I think that number will probably go up, it’s just how high is hard to say.”

How did Hurricane Milton develop?

Like Hurricane Helene a week before, Hurricane Milton was the beneficiary of higher-than-average ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, an already warm body of water. These warm temperatures are fodder for hurricanes, which tend to develop when water surface temperatures are 82° Fahrenheit (27.8° Celsius) or higher.

“Milton was a near-perfect case [for tornado formation], especially for Florida, given its orientation and timing.”

Milton also benefitted from a low vertical wind shear during its formation, meaning that there wasn’t much difference in the speed or direction of wind acting on Milton at different altitudes. That helped the storm build vertically, churning from a Category 1 hurricane into a Category 5 storm (with winds exceeding 175 miles per hour, or 282 kilometers per hour) in less than a day.

Hurricane season runs from June 1 through November 3, meaning we may be in for some more large storms out of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean before all is said and done. Both NOAA and Colorado State University predicted a much busier-than-average hurricane season, meaning the expected number of named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes were higher than 1991 to 2020 averages.

Hurricane Milton created “near-perfect” conditions for tornadoes

Thompson said that Milton’s tornado frenzy came down to a—sorry in advance for the clumsy cliché—perfect storm of factors.

For one, Hurricane Milton charted a pretty untraditional path as it rapidly grew from a hurricane seedling in the western gulf to a Category 5 hurricane off Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. Most hurricanes hitting Florida originate in the Atlantic—to the east or southeast—but Milton approached from the southwest, having formed off far west in the gulf.

“Normally we’re talking about a few weak tornadoes” in the event of a tropical cyclone, Thompson said. But Milton’s rapid expansion meant that as the storm encroached on Florida, its outer spiral bands arrived over the state in the afternoon. “With a little bit of sunshine in between them,” the thunderstorm bands were able to heat up even more than usual. Combined with increasing winds, the atmospheric cocktail set up a tornado threat.

“If you’d had the same movement [in the hurricane] and we just offset it by 9 to 12 hours, there are probably still some tornadoes, but it’s knocked down quite a bit from what we had,” Thompson said.

But that’s not all, Thompson said. To the north of central Florida, the atmosphere “amounted to a weak frontal zone,” a cloudy region with cooler temperatures and rain. A common pattern for tornado formation happens when storms come out from the south and interact with a frontal zone, causing clusters of tornados.“Usually the more favorable area for tornadic storms in a hurricane is on the side of the storm where you’re bringing the warmest and the most moist air towards the poles,” Thompson said—basically the east or northeast side. The side of the storm that’s less likely to cause thunderstorms—and therefore less likely to cause tornadoes—typically makes landfall first. But that wasn’t the case with Milton.

With those north- or northwest-moving storms, the most likely tornado threat is near or after landfall, Thompson added. In Milton the opposite happened. The conditions favorable for tornado formation—those thunderstorms carried ashore by warm, moist gusts of winds—arrived from the west, before the hurricane itself made its eastward march across the state.

So in sum: The tornadoes were a particularly bad combination of a very unusual hurricane path, a rapid intensification and expansion of that storm, and the timing of the arrival of those hurricane-force winds and storm clouds over an area already warmed up by daytime temperatures.

Okay, geez. What’s the good news?

There’s not much to claw at here except that the storm has passed. We’re not getting a Hurricane Harvey-esque stall-out over Tampa Bay or Port St. Lucie that caused Houston to flood in 2017. There’s no threat of tornadoes today—in fact, Thompson said, the “carcass” of the hurricane is pulling cooler, drier area from its south side, which is why today is “relatively nice by Florida standards.”

But should future storms hit Florida from the west, instead of the south or east, you can expect a similar sort of pattern to unfold–especially if the storm approaches in the afternoon, and with the sea temperatures as warm as they are these days.

Read the full article here