Astronomers at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy just constructed a detailed, three-dimensional map of the cosmic dust in our galaxy.

The map makes use of 130 million spectra from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission to reveal properties of the dust, which clouds the cosmos between our world and just about everything else in the Milky Way. The 3D map indicates where the cloud most muddies the waters of the cosmos, as well as charts the regions where the “extinction” of light is less affected by the particulate matter. The team’s research was published today in Science.

The dust distorts our view of stars and other bodies, making them appear redder and fainter than they really are. The latter effect is also known as extinction, or the absorption and scattering of background light by intermediate objects—in this case, dust grains.

Of the 220 million spectra released by the Gaia mission in June 2022, the research team selected 130 million stars that they determined would be useful for their dust search.

The researchers then trained a neural network—a machine learning system that draws conclusions by mimicking the processes of neurons in a brain—to generate spectra based on the properties of the smaller group of stars, along with the properties of the dust itself.

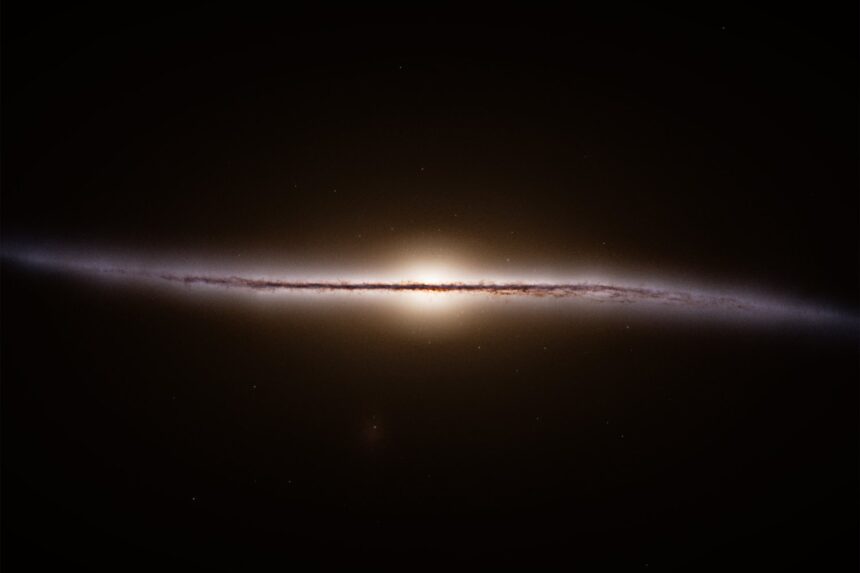

The visualization above shows how the extinction curve caused by dust manifests itself around our Sun, up to 8,000 light-years in every direction. Red regions in the graphic show where the extinction of light is more dependent on the wavelength of the light, whereas extinction is not so dependent on wavelength in blue regions.

Grey contouring shows areas of higher dust density in the map. And if the graphic above makes you lose sight of the grandeur covered in this part of the universe, just look at the Webb Space Telescope’s arresting shot of the Carina Nebula (at the bottom of the above image).

According to a Max Planck Institute release, the 3D map also revealed that the extinction curve for denser regions of dust (corresponding to a little over 20 pounds, or 10 kilograms, of dust in a sphere with Earth’s radius) was steeper than expected. The researchers suspect the steep curve may be caused by an abundant form of hydrocarbon in the cosmos—a position they hope to understand with more observations.

Gaia collected more than three trillion observations of the Milky Way between July 24, 2014 and January 15, 2025, after which the intrepid spacecraft promptly retired. Gaia’s data helped scientists produce the best reconstructed view of our galaxy as it would appear to an outside observer in January, but mapping is not all it did: The telescope also has a great track record with black holes, helping researchers identify the heaviest stellar-mass black hole in April 2024 and spotting the closest-known black hole to Earth in 2022.

Read the full article here