The famous skeleton of a child with human and Neanderthal features has now been precisely dated, thanks to a new radiocarbon dating technique that provides a more accurate timeline of the child’s life.

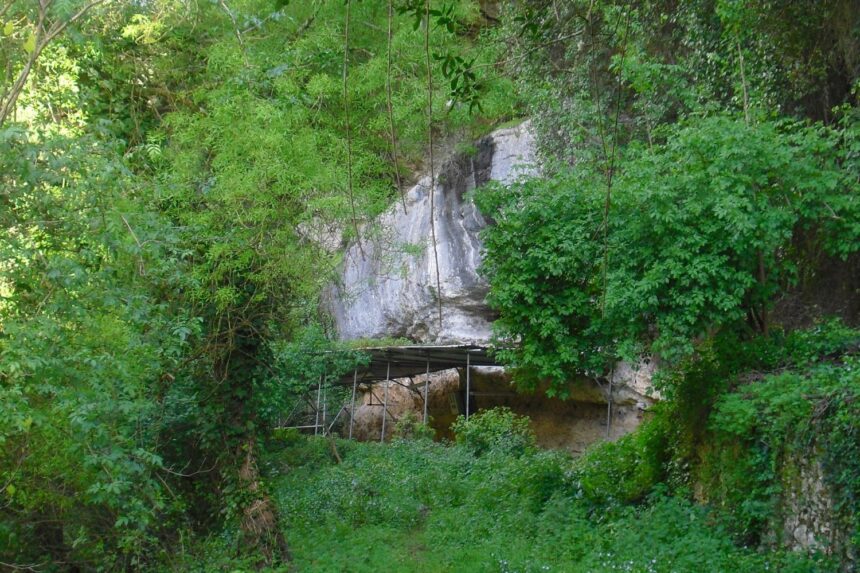

The Lapedo Child—so-named for the valley in Portugal in which it was found—was discovered in 1998, when students chanced upon the rock shelter that contained the remains. Excavations revealed the child’s nearly intact, ochre-stained skeleton, as well as animal bones, charcoal, and beads made from marine shells. But despite recovering a significant number of the child’s bones, archaeologists found the remains in relatively poor condition—meaning that until now, scientists have not been able to reliably date the child.

The child was part of the Gravettian culture, which persisted across Europe between 32,000 and 24,000 years ago, and is perhaps most well-known for their voluptuous Venus figurines. Despite the Gravettian culture’s presence for thousands of years, Gravettian groups across the continent were not closely related, as one 2023 genetic analysis showed.

Pinning down the age of the Lapedo Child would be useful in a couple of ways: for one, researchers would know exactly when the population to which the child belonged inhabited the Portuguese coast. And secondly, the researchers would prove out a method that could then be applied to other Gravettian and Cro-Magnon populations across Europe, revealing a more comprehensive timetable of early modern human occupation and migration across Europe.

“The fact that only a small amount of collagen (the organic part of the bone) could be extracted from the child’s bones, combined with the fact that the contamination couldn’t be fully removed meant that the original dates were not reliable,” said Bethan Linscott, a researcher at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at the University of Oxford and lead author of the study, in an email to Gizmodo.

Scientists have attempted to calculate a reliable radiocarbon date for the Lapedo Child on four different occasions, each unable to nail down a reliable timeframe. The latest team believes they’ve done it, though, using a new dating method that reduces the impact of contaminants in the sample and targets specific amino acids to determine the sample’s age.

“We were able to obtain a reliable direct date for the skeleton using a relatively new technique called compound-specific radiocarbon dating,” Linscott added. “Normally, collagen is extracted from bone and dated in bulk, but this method involves extracting a specific amino acid from the bone collagen—called hydroxyproline—and dating that instead. Hydroxyproline is rare elsewhere in nature and essentially acts a bit like a collagen ‘fingerprint’, so by dating hydroxyproline, we can be sure that the carbon we’re dating is coming directly from the bone and not from contamination.”

The child was a survivor, even in death: According to the research team, the site where the remains were found was terraced by the landowner to build a shed several years earlier. Nearly 10 feet (3 meters) of archaeological material was destroyed in the process, but the child’s burial got by unscathed.

The team’s analysis of the child’s right radius (one of two large bones in the forearm) yielded a new date estimate for the individual’s 4-or-5-year-long life: between 27,780 and 28,850 years ago.

“The new date for the child is consistent with original estimates for the age of the burial, but it has changed our interpretation of the burial events themselves,” Linscott told Gizmodo.

The charcoal beneath the child, for example, was previously thought to be a ritually burned twig for the Lapedo Child’s grave. But the charcoal predates the child. The grave also contained red deer pelves—thought to be meat offerings, but also older than the child.

Linscott noted that the pelves still may have been placed there intentionally as part of the burial—perhaps as support—and the rabbit vertebra dates indicate that the animal was placed ritually, perhaps as a symbolic offering for the grave.

Hydroxyproline dating can be used to recalibrate the timing of human presence across Europe (and beyond) with precision. The method has been used on Neanderthal groups—Neanderthal remains in Croatia’s Vindija Cave were thought to date to about 29,000 years ago, well past the general estimate for Neanderthals’ disappearance around 40,000 years ago. In 2017, a group of scientists used hydroxyproline dating to find that the Vindija remains were indeed older than 40,000 years, indicating that the Croatian find did not usurp general consensus about Neanderthals’ timeline.

The approach could continue to refine scientists’ understanding of early modern humans and Neanderthals’ movements and occupations across the continent, and perhaps can help refine estimates of ancient human relatives worldwide in the future.

Read the full article here