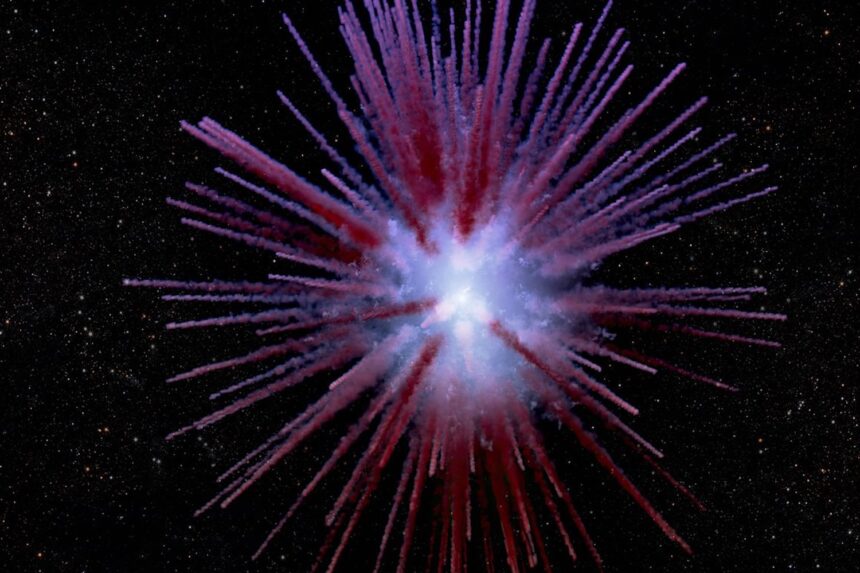

Somewhere out in deep space, there’s a beautiful cosmic weed, blasting its metaphorical pollen away from its core at ludicrous speeds. For almost 900 years, the massive space explosion that caused this weed to bloom was a mystery. Now, a cutting edge telescope is providing our best look yet at the results.

The weed is actually a nebula, named Pa 30 nebula, and its shape has some eccentricities. In 2023, astronomers from Dartmouth College and Louisiana State University described the matter blasted away from the explosion as clumping together into filaments, which sprout from the center like the puff of a dandelion. Following up on that research, other astronomers have now mapped those filaments for the first time.

Humanity’s interest in the nebula can be traced back to the year 1181, when astronomers in Japan and China both recorded seeing a new star. After six months, it was gone, but not forgotten. In 2013, an amateur astronomer named Dana Patchick was looking at images taken by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, a now-decommissioned infrared space telescope. He identified a nebula in the region of space where the star may have been, 7,500 light years away from Earth, in the Cassiopeia constellation. In the decade that followed, astronomers concluded Pa 30 nebula was likely the remnants of a supernova, which the ancient astronomers had witnessed all those years ago.

Nebulas are brightly glowing, and frequently gigantic, collections of matter, such as ionized gas and space dust. But not all nebulas are alike. Some are composed of the remnants of stars, which die in massive explosions. That’s what happened in Pa 30 Nebula’s case, and some of the results are unique among known nebulae. At its core, a remnant of its birthing star remains, with a surface temperature of 360,000 degrees Fahrenheit (200,000 Celsius). For reference, our Sun has a surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 Celsius). The star is also shooting material away from itself at the ludicrous speed of 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) per second.

“We find the material in the filaments is expanding ballistically,” said Tim Cunningham, a NASA Hubble Fellow at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in a statement. “This means that the material has not been slowed down nor sped up since the explosion. From the measured velocities, looking back in time, you can pinpoint the explosion to almost exactly the year 1181.”

Cunningham and his colleagues wanted to get a better idea of the shape of those filaments. They turned to a device in Hawaii called the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI), which detects light in the visible spectrum. Different colors move with different amounts of energy. For instance, blue has relatively high energy levels compared to red. The difference in energy allowed the astronomers to map out which matter was moving in the Earth’s direction, and which was moving away. The result was a 3D map of the nebula’s filaments. The shape is asymmetrical, which hints that the original explosion was also asymmetrical. There’s also a weird cavity of nothingness, that’s up to 3 light years wide, between the star remnant in the middle and the filaments, which is likely the result the explosion destroying all the matter that was too close to its center. (It should be noted Pa 30 nebula is hardly alone in being a celestial body with a weird shape.)

“A standard image of the supernova remnant would be like a static photo of a fireworks display,” said Christopher Martin, a professor of physics at Caltech, who worked on the ensuing study, which was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “KCWI gives us something more like a ‘movie’ since we can measure the motion of the explosion’s embers as they streak outward from the central explosion.”

The question that remains is why this nebula took on this shape. Cunningham said it could be because a shock wave condensed the speeding dust into beams, but nothing is certain. Even after almost a millennium, some mysteries continue to persist.

Read the full article here